An accident led to her premature labor her baby prematurely. Then came the postpartum depression … 2025

An accident led to her premature labor her baby prematurely.

Kysten Alvarez was seven and a half months pregnant with her first child when a life-altering accident occurred. She fell down the stairs, breaking four bones in her foot.

Just hours later, doctors performed an emergency C-section to deliver her baby boy.

Alvarez spent five days in the hospital while her newborn was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). But going home brought new challenges.

Wearing a cast,

she couldn’t even bathe her baby—let alone care for herself. Overwhelmed by guilt and despair, she began experiencing the early symptoms of postpartum depression.

“I kept thinking, ‘I’m not enough. I’m not a good mom because I can’t take care of my baby,’” Alvarez recalls. “Everything felt like it was getting worse.”

At one point, she told her family — her mom, sister, and husband — that they would be better off without her. She even packed a bag, planning to leave for a homeless shelter, convinced she was a burden.

“I hate saying it out loud because that’s not who I am,” she says about that dark period in 2023.

Cultural Expectations and Mental Health Stigma

Alvarez grew up in a Latina family where being “tough and strong” was expected. Her mother and grandmother had raised children while working full-time, never asking for help or relying on therapy. So, when Alvarez struggled after giving birth, she felt like she couldn’t speak up.

“Why can’t I do this? They did it with less support,” she remembers thinking.

Research shows she’s not alone. According to a 2016 study in the Journal of Racial and Health Disparities, Latina women in rural areas face a 40% higher risk of postpartum depression than the general population.

A 2013 study in the Journal of Affective Disorders found that 13% of women overall experience postpartum depression, but among Latina immigrants, the rate skyrockets to 54%.

Despite this,

Latina women are less likely to seek mental health treatment. Data from the National Alliance on Mental Illness shows only 35.1% of Hispanic/Latinx adults with mental illness access care annually, compared to 46.2% of the general population.

Why Postpartum Depression Often Goes Undiagnosed

Dr. Ingrid Parades, an OB-GYN specializing in postpartum mental health, says cultural stigma often prevents women from opening up about their struggles.

“As healthcare providers, we sometimes have to play detective,” she explains. “Patients downplay symptoms because in many cultures, needing help is seen as weakness. Even when we offer support, it can be hard for them to accept it.”

Alvarez herself admits she resisted help at first. She had seen a therapist early in her pregnancy for anxiety and ADHD but stopped treatment and medication out of concern for her baby’s health.

“When I saw how much pain my family was in because of my depression, that’s when it hit me,” she says. “I realized I needed to get better for them as much as for myself.”

Struggling to Find the Right Support

Alvarez attended a postpartum depression support group but felt her experiences didn’t compare to others. Some mothers expressed anger or resentment toward their babies—emotions she couldn’t relate to.

“I told myself I wasn’t really dealing with postpartum depression, that I was just weak,” Alvarez says. She left the group without continuing therapy, convinced her struggles weren’t serious enough.

Meanwhile, social media made things worse. Her friends posted happy updates about marriages, pregnancies, and motherhood milestones. Alvarez felt like she was the only one falling apart.

Readmore PM Vehicle Policy Electric Bike and Rikshaw Scheme New Energy 2025-30

Breaking the Silence Around Postpartum Depression

Kysten Alvarez’s story reflects a bigger issue: the intersection of cultural expectations, mental health stigma, and postpartum care gaps for Latina mothers. Too often, women silently endure depression, believing they must be strong like the generations before them.

Experts stress the importance of accessible mental health resources, culturally sensitive care, and open conversations about postpartum depression. Seeking therapy, joining support groups, or speaking openly with family can be lifesaving steps for mothers struggling in silence.baby

After experiencing severe postpartum depression following her first child’s birth,

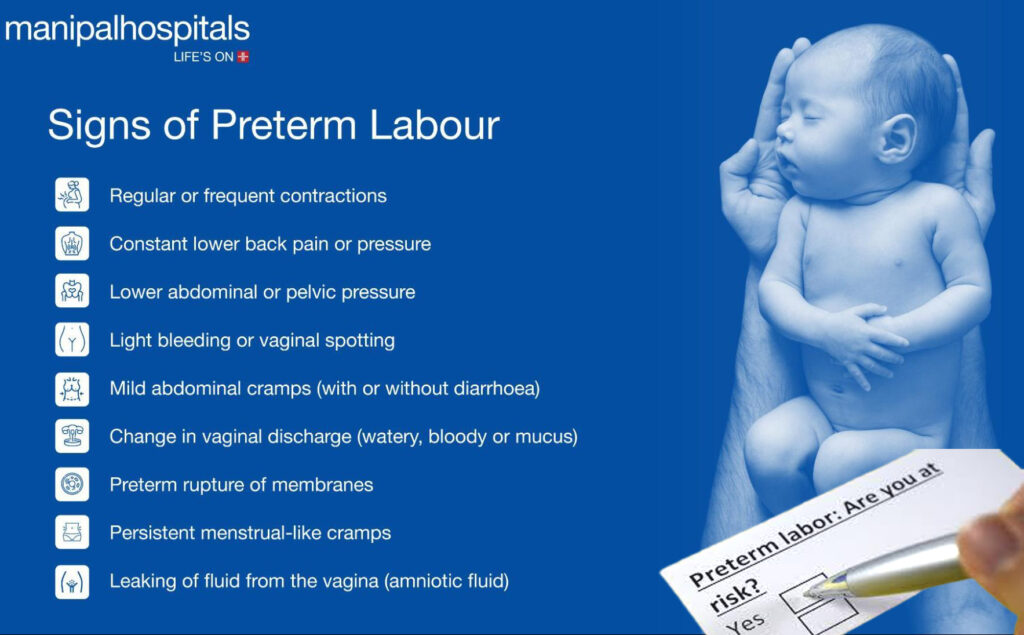

Kysten Alvarez thought she could push her feelings aside. But during her second pregnancy, complications returned. This time, it wasn’t just depression — she developed preeclampsia, a condition that led to another early delivery.

When her newborn, now 6 months old, had to be admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), Alvarez says she felt like she couldn’t do anything right.

Doctors repeatedly asked how she was coping.baby

Her answer was always the same: “Everything’s great.”

But behind the scenes, Alvarez was struggling in silence.baby

“I don’t like to show struggle because I grew up thinking struggle was weakness,” she explains. “It felt like everything was on me again. It was easier to blame myself than accept something I couldn’t control.”

When Family Stepped In

Alvarez’s husband finally spoke up during a doctor’s appointment.

“He told them, ‘She puts on a smile here, but at home, she cries all day,’” she recalls.

That intervention became a turning point.

Alvarez was exhausted, physically and emotionally, and needed real support.

Zurzuvae is a synthetic version of allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid derived from the hormone progesterone.

After childbirth, hormone levels drop significantly, and research shows these changes can trigger postpartum depression symptoms in vulnerable women.

Alvarez hesitated for weeks before opening the box.

Her extended family strongly discouraged her from taking the medication.baby

“They told me I was crazy. They said, ‘You don’t know what that medicine will do to you.’”baby

But Alvarez knew she couldn’t keep “suffering in silence” the way previous generations in her family had.

“My mom and grandma always carried on like nothing was wrong. But it was destroying me inside.

Cultural Barriers to Mental Health Treatment

Dr. Ingrid Parades, an OB-GYN and postpartum depression specialist, says stigma around mental health treatment exists in every community. However, among Latina mothers, family opinions often carry extra weight in deciding whether to seek care or take medication.baby

“Some husbands don’t believe in therapy. Some mothers normalize the suffering,” Parades explains. “I’ve seen patients get worse because they felt too much pressure to ‘tough it out.’”baby

Learning That Asking for Help Is Strength

Alvarez says accepting treatment helped her heal — and also taught her that self-care isn’t selfish.

She compares it to the advice given on airplanes: put your own oxygen mask on first before helping others.